The Well-Traveled

Confederate

One famous Confederate general, however, refused to surrender in the aftermath of Appomattox. General Jo Shelby, a native Missourian, gained fame during the Civil War for his leadership of his “Iron Brigade” in daring cavalry raids, especially Shelby’s Great Raid in the fall of 1863, which wrecked havoc in Missouri. Shelby, famous for the black ostrich plume he wore on his hat, instead of surrendering, led several of his soldiers to Mexico.

John W. Coshow, who spent almost all of his life in Boone-Duden country, was one of those soldiers. Over forty years after the end of the Civil War, Coshow responded to a St. Louis newspaper’s request for the recollections of former Confederates. In late January of 1908, he wrote this letter to J. W. Allen, the editor of the St. Louis Republic, which told the story of his time in Mexico (Spelling, punctuation, and grammar have been altered for clarity. Explanatory notes have been inserted into the letter in bold type.) The original letter may be viewed online at http://collections.mohistory.org/bookreader/br/?item_id= http%3A%2F%2F collections. mohistory.org%2Fresource%2F173257#page/1/mode/1up).

Dear sir — I see by the St Louis Republic of January 27th your call for Missouri Confederates to assist in compiling a roster of those that served in the Confederate Army. I will do what little I can towards that object. First, in October 1864, Col. Caleb Dorsey and Col. Hull were recruiting here in St. Charles County (and adjoining counties). I, with between 150 and 200 others, joined their force and started with the intention of joining Price’s army, which was then making its last raid in Missouri. [When the Civil War began in 1861, John Coshow was the fourteen year old son of slave-owning parents Jackson and Eliza Coshow of Femme Osage. Perhaps he chafed at home as many of his neighbors went off to war, but his chance to enlist finally came in the autumn of 1864 when, at the age of seventeen, he joined the Confederate cause.] The intention of joining Price below Booneville was frustrated by a large body of Federal cavalry that surrounded us in Boone County, Missouri. Thanks to a big snowstorm late in the evening, it gave us an opportunity to slip out and follow down Cedar Creek, and the falling snow obliterated our track, which saved our bacon. We succeeded in swimming our horses across the Missouri River but not in time to take a hand in the fight at Booneville. [The new recruits, most of whom were unarmed, apparently followed the Missouri River to the Columbia area in Boone County. Cedar Creek is in the southern portion of the county. Significant snow was recorded in northwestern Arkansas on November 2, 1864, so Coshow’s narrow escape may have occurred then.] Then the Federals were between us and Price, so we bore south, through Rolla and Licking, where we met with some troops that had been following Price. After a slight scrap we got through and reached the Army of Price at Fulton, Arkansas. [Licking is in Texas County, Missouri, and Fulton, Arkansas, is in the southwestern corner of the state, only a few miles from Texas. As they attempted to join Price, many recruits were killed by Union soldiers.]

|

| Coshow in 1905 |

There the Army was reorganized. Some were dismounted and put into the infantry. There Slayback’s Regiment was organized. Most all of us, recruited by Dorsey and Hull, were put into Slayback’s Regiment (with Caleb Dorsey as Lieutenant Colonel) in two companies: Company A commanded by Ras. Woods of St. Charles County, Missouri, and Company E commanded by Miles Price of Henry County, Missouri. [Coshow was enrolled in Company E of Slayback’s Regiment.]

Just after the reorganization, I was detailed to Brigade Headquarters, as orderly to Col. B. F. Gordon, who was then in command of Shelby’s Brigade, while Shelby was in command of the division. It was not generally known that Shelby was promoted and also B. F. Gordon was promoted to fill Shelby’s old place, just before Lee’s surrender. Being at brigade headquarters I was aware of the fact. I cannot say for certain if Shelby and Gordon ever received their official promotions, but at the time of our disbandment at Corsicana, Texas, B. Frank Gordon was in command of four regiments and one battery, to wit Gordon’s Regiment, Shank’s Regiment, and Collins’ Battery of four brass cannon (two rifled and two smooth bore). I don’t remember the other brigade and battery that was under Shelby at the time. I wish someone would inform me what other four regiments and battery that were commanded by Shelby, as there were certainly two brigades and two batteries under him. And I do know that one of them was Shelby’s old brigade and Collins’ Battery, which formed half of our division. I would like very much to get at the other half in some way. I suppose after the Government print comes out I will see who they were. [Corsicana is in northeastern Texas.]

I have often read in papers of writers wondering why Price and Shelby went to Mexico instead of going to Shreveport and surrendering as most of our command did. I will tell them. General Price thought it a good idea to go to Mexico and get a grant of land, start a colony and have our families come to us, not knowing if we would be allowed to return to Missouri and live again. Now that is the reason they went to Mexico, and that is the reason that some 300 or more of us went with them. [Another possible reason Price and Shelby had for going to Mexico was to establish a base for reinvasion of the United States.]

One morning we broke camp at Corsicana, Texas. The bulk of our command went to Shreveport and was surrendered to the Federal commander by Captain Adams, he being the ranking officer that surrendered. All officers above Captain Adams went with us to Mexico. We passed through San Antonio and crossed the Rio Grande at Eagle Pass. [At Corsicana on June 1, 1865, General Jo Shelby announced to his assembled command that he would not surrender to Federal authorities but would instead go to Mexico. He instructed any soldiers who would follow him to Mexico to step forward three paces; about one hundred fifty men did so, including almost all of his officers. As the small command crossed Texas, passing through Waco, Austin, and San Antonio, it was joined by soldiers from other units; some families seeking safe transport out of the Confederacy; and several politicians, including the governors of Texas, Louisiana, and Kentucky. The group, now numbering several hundred, arrived at Eagle Pass, Texas, on June 25, 1865, and camped on the American side of the Rio Grande River, facing Piedras Negras, Mexico.]

War was raging in Mexico at the time between the Maximilians (or Imperials) against the Mexicans (or Liberals). [A year earlier, in 1864, the French had placed their puppet emperor Maximilian on the throne of Mexico. Shortly after the French withdrew their army in 1866, Maximilian was captured and executed. The Liberals were led by Benito Juarez.] The Liberals, being in possession of Piedras Negras (opposite Eagle Pass) would let us pass over into Mexico only with our side arms (sabers and revolvers). They offered to buy all the other arms. We had several cases of Springfield rifles that had never been opened and two of the guns of Collins’ Battery that we had taken along (the other two we had spiked and left at Corsicana) with several six-mule CSA teams and wagons. We being the only men that had not surrendered contended was ours by right to sell or dispose of at our own pleasure. We sold all to the Liberals. Got enough when equally divided to amount to seventy-five dollars each in gold and silver. [On June 26, 1865, Shelby sold three artillery pieces, forty wagons of Enfield rifles, and a large wagon train to the Liberals. Shelby was offered a major generalship in the Liberal army and authority to recruit 50,000 Americans to fight against Maximilian, which he considered accepting. However, his soldiers almost unanimously supported Maximilian’s Imperial forces, so Shelby declined the offer. A few days later, Shelby assembled his command at the Rio Grande River and, in an intensely emotional ceremony, the division’s battle flag was wrapped around a large boulder and sunk in the river; inside the bundle was Shelby’s black plume. The next day, July 4, 1865, the Confederates crossed into Mexico.]

We then marched to Monterrey which was in the possession of the Imperials who were more friendly to us than the Liberals, they offering Shelby big inducements to join with them with all or as many of his men that were willing to join (and that would have been every man who had followed his ostrich plume in the States), but when General Price heard of the transaction he called us all together and stated his views so plain that Shelby gave way. Pap Price, that “Grand Old Leader,” was right. I see it all. We would all have been outlawed and never could have been citizens of the US if we had not taken his advice. [Shelby’s force marched to Monterrey, which was held by the Imperials. The French offered the Confederates a tantalizing proposition: if at least 250 men would enlist in Maximilian’s army, each man would receive a $600 bounty and $100 per month in pay. In comparison, the pay for a Confederate enlisted man at the end of the war was only $18 per month. However, not enough Confederates were willing to enlist, so the deal fell apart.]

General Price left us at Monterrey and went on to the City Mexico to see about getting the grant of land, but after trying some time without success on account of the unsettled condition of the country, he finally wrote that he could do nothing at present and advised us to make our way back to the United States and surrender to the government. Some scattered over Mexico, some started on our way back to Eagle Pass. Many of this rank never lived to reach the Rio Grande, being killed by the renegade Mexicans that swarmed all over the country at that time. I with three others (Dr. Marks of Kentucky of Williams Regiment being one) went to Matamoras and surrendered to Colonel Black, commander at Brownsville, Texas, who paroled us. I have my parole yet and will keep it through my life. [A few weeks later, Shelby was ordered by Imperial army to report to the Emperor Maximilian in Mexico City. There, Shelby offered his services to Maximilian, but the emperor declined, fearing a backlash from the American government, whose support he needed in his battle against the Liberals. The French then gave each of Shelby’s men fifty dollars, and Shelby’s military expedition was officially over. The Confederates dispersed in several directions. Some went to California, some to South America, and some “unofficially” joined ranks with the Liberals or Imperials. Shelby encouraged settlement in a farming area near Vera Cruz, where he and Sterling Price lived with several Confederate families on land provided by the French. Jo Shelby returned to Missouri in 1867.]

Now, Captain, I don’t suppose any of this will interest you in the least but thought some little thing I have scratched will help you in your task has induced me to write this. I have but a limited education (as you can judge) but it’s the best I can do. At least I can give you my name and command I belonged to. I hope some that followed Price and Shelby to Mexico are still living, but I do not know of a single one but myself. [The key word here is living. Coshow very likely knew quite well William Wallace, another Confederate from Boone-Duden country who went to Mexico after the war, since the Wallace and Coshow families lived only a short distance apart in Femme Osage Township. Wallace had died in 1879.] If others are living, I would like so much to meet them, or at least correspond with them. If I have made any mistakes, I hope someone will correct me. It’s as I recollect the incidents and don’t think I am far wrong. Enclosed find statement of my enlistment and am yours truly.

John W. Coshow

Howell, Missouri

When John Coshow left Mexico in 1865, he may have initially tried to return to his parents’ home in Femme Osage Township, but if he did, he apparently did not stay long. After the war, the Missouri legislature, controlled by the Radical Party, rewrote the state constitution, which included a loyalty oath, the “Ironclad Oath,” required of any former Confederate who wished to have full citizenship in Missouri. The oath required the person to swear he had not committed any of nearly ninety different acts of disloyalty, including even expressing support for the Confederacy. If he did not take the oath, the former soldier could not vote, practice law, serve on a jury, teach, manage a corporation, or serve as a minister. Obviously few former Confederates could truthfully take the oath, and John Coshow was not one of them.

If he could not return to Missouri, where could Coshow go? In the 1870 federal census, John Coshow was living hundreds of miles from his home in Missouri. Sometime after he left Mexico he went to the Montana Territory. What could possibly have motivated Coshow to settle over 1,300 miles from his boyhood home in Missouri?

As Sterling Price’s army disintegrated after his failed invasion of Missouri in 1864, the Union commander in the state, General Alfred Pleasonton, faced the unpleasant prospect of dealing with perhaps hundreds of former Confederates practicing guerrilla warfare in his jurisdiction. So Pleasonton created an amnesty policy, allowing soldiers captured from Price’s army freedom, as long as they promised never to fight again and, most importantly, that they depart Missouri and go to the Dakota or Montana Territories. Pleasonton’s hope was that Confederates in the state would voluntarily surrender and leave. By this time news of the 1863 discovery of gold in Montana Territory had reached Missouri, so many Confederates accepted the amnesty and went to Montana. One historian writes, “The gold rush had brought so many Missourians to Montana that the saying Montana was settled by the left wing of Price’s army bears an element of truth.” By war’s end the territory had a “very vocal southern anti-Union crowd.” In fact, the territorial capital was named Virginia City in 1863 because of this southern element in Montana.

John Coshow must have known of the Pleasonton amnesty as he worked his way north after leaving Mexico. It is very probable he knew of some former Confederates who had taken advantage of the amnesty and gone to Montana Territory. (Although he was not a former Confederate, Lewis Howell, from Dardenne Township, had moved with his family to Montana Territory around 1865; since Coshow and Howell were cousins, it is likely Coshow knew of Howell and his departure west.) Coshow, upon his return to Missouri, was faced with the Ironclad Oath, to which he could not swear, so he decided to go west, knowing he would find a likeminded community of southern sympathizers in Montana Territory. The Gallatin Valley is situated about eighty miles east of the gold fields of Virginia City, and the trail to the gold went through Gallatin County. Many Confederates-turned-prospectors eventually returned east to Gallatin County to farm the rich soil; this may have been what happened to John Coshow. In January of 1870, Coshow, now a landowner, married Alice Ferguson, a fifteen year old from Kentucky, in Gallatin County. The next year their first child was born in Gallatin County. Living in the same township was the Lewis Howell family.

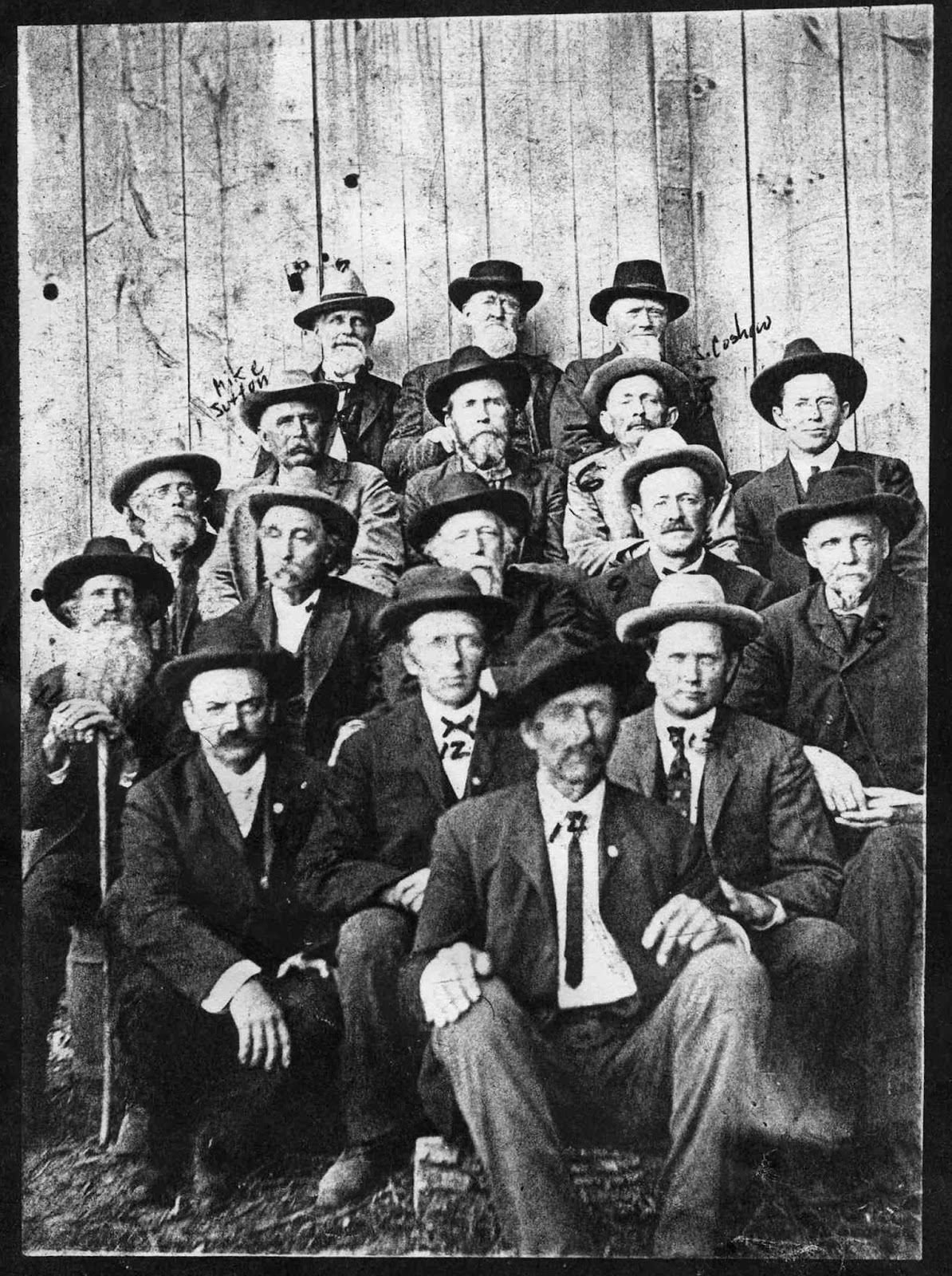

|

| Coshow is 2nd from the right in the 2nd highest row |

The United States Supreme Court had ruled in 1867 that the new Missouri constitution was unconstitutional, and Missouri voters themselves had repealed the loyalty oath in 1870, so sometime during 1871-1873, Coshow returned to Missouri with his wife and infant son. They owned a farm in Dardenne Township until sometime before 1920 when, for unknown reasons, they bought a farm in Branson Township, Taney County, in southwestern Missouri. When both Alice and John Coshow died in the mid-1920’s, they were buried in the Thomas Howell Cemetery, now located in the Weldon Spring Conservation Area.

It is remarkable to think that one of the celebrated Jo Shelby’s soldiers lived in the Boone-Duden area for almost his entire life. John W. Coshow, a patriotic teenager who enlisted when the war was nearly over, marched to Mexico and later made his way to Montana before returning to Missouri. He was certainly a well-traveled Confederate.

Sources: 1860 slave census; 1876 Missouri State Census; 1905 St. Charles County Plat Maps; “Antecedents and Descendants of Judge Gordon H. Wallace “1807-1888” (Lewis R. Howell); bozemanmontanarealty.com/history; familysearch.org; Federal Censuses; General Jo Shelby’s March (Anthony Arthur); history.state.gov/milestones/1861-1865/french-intervention; Jo Shelby’s Iron Brigade (Deryl P. Sellmeyer); Lost Cause: the Confederate Exodus to Mexico (Andrew Rolle); mtpioneer.com/2010-Nov-confederate; nps.gov/fosu/forteachers; wikipedia.